In this article, I am not using the terms “feminine” and “masculine” as related with gender or sex. Masculine and feminine “traits” are concepts or archetypes that developed in numerous cultures over millennia. They may be useful as intellectual models by which we might analyze particular aspects of human behavior, but they can also easily be misused in ways that restrict or misrepresent well rounded or full expressions of human nature as it has existed in many forms. Much of what has been described by these ideas or paradigms can be observed regularly in all people, not just one particular gender or sex. Humans are psychologically androgynous, in that every person contains both of what many civilizations have termed “feminine” or “masculine” elements. The interaction of these characteristics or features can be seen in every field of life: relationships, science, history, philosophy, business, religion, sports, politics, etc. Related to human physiology, males and females possess both estrogen and testosterone in great variation per individual. It is deeply inaccurate to limit gender or the archetypes of masculinity or femininity to just one sex.

The discussion below is based on the conceptual or archetypal ways that masculinity or femininity have many times been utilized in philosophy, religious studies, psychology, and theology to explore how various parts of human thought and action can be seen, ignored, appreciated, or diminished as a result of foundational presuppositions in the worldview of an individual or entire society. Thus, feminine and masculine archetypal descriptions can be applied to any element of culture. They can also be used to categorize non-human aspects of nature.

To have a society, philosophy, or religion that is vigorously strong and realistically grounded in the common patterns of human nature, all other components of the cosmos, and the ontological traits intrinsic to any deities that might exist, a thorough and dynamic combination of feminine and masculine fundamentals ought to be remembered, maintained, valued, and engaged.

These archetypes can often be useful and insightful frameworks when discussing the varied forms of things in the natural world: air molecules, rocks, squirrels, oceans, planets, etc. Investigating reality through paradigms like these can reveal that masculine and feminine archetypal elements are present everywhere in the universe, from the quantum level to the macro scales of solar systems and galaxies. Any possibly existing gods that are connected with this universe, either presently or only in the original design, would have to contain both feminine and masculine qualities either by themselves or collectively in order to produce the living and non-living things and physical laws that make up an environment such as ours.

Many of the practical, structural, and ideological components of world culture since the Agricultural Revolution of 8,000-10,000 years ago have greatly over-emphasized the masculine archetypal side of reality. This has caused much damage, error, and distortion. These models and practices existed in a vast number of premodern civilizations and still can be found in most nations to a considerable degree.

Different problems can happen because of a lopsided focus on the feminine archetype, but this category has generally been suppressed or resisted since the first cities were populated. Anthropologists often say that earlier forms of human organization, specifically in hunter-gather communities, were significantly more egalitarian in behaviors, values, and religious orientations. Many historians point to a gradual re-emergence of the feminine archetype occurring in the past 250 years in Western nations beginning with the 18th-19th century Romantic period in philosophy, literature, art, and music, and being further developed especially in the cultural revolutions of the 1960s. There is wide room for legitimate debate regarding how much emphasis on the feminine and masculine archetypes was present in both Eastern and Western cultures over the millennia.

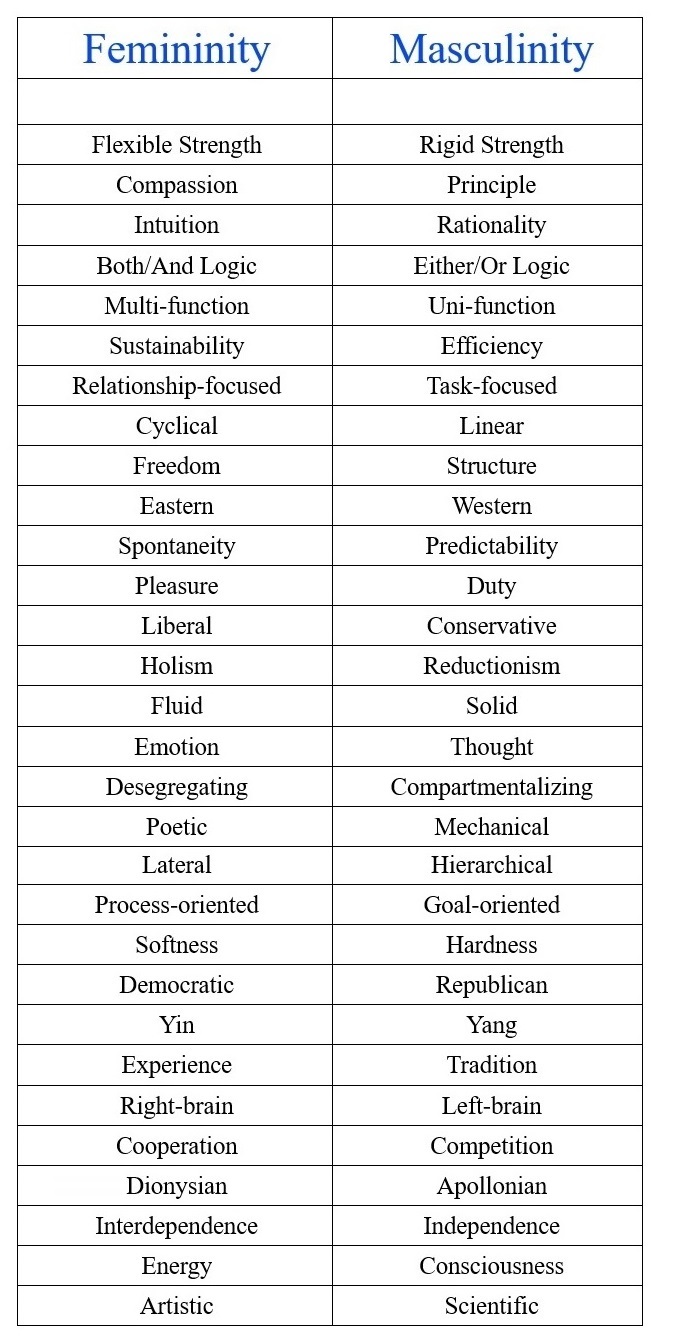

The table below details a variety of ways that masculine and feminine archetypes may be understood and engaged in theory and practice.